Franco Angeli ed. | Estratto google books

Infrapedia | Trademark | Facebook

A cura di: Francesco RampichiniScritti di: Ettore Lariani, Marco Maiocchi, Francesco Rampichini

COS'E' L'ACUSMETRIA

Acusmetria sf. (dal gr. "akouo", udire e "metréo", misurare). Neologismo introdotto nel 2002 da F. Rampichini, a indicare il codice delle proporzioni geometriche nella rappresentazione acustica della prospettiva spaziale.

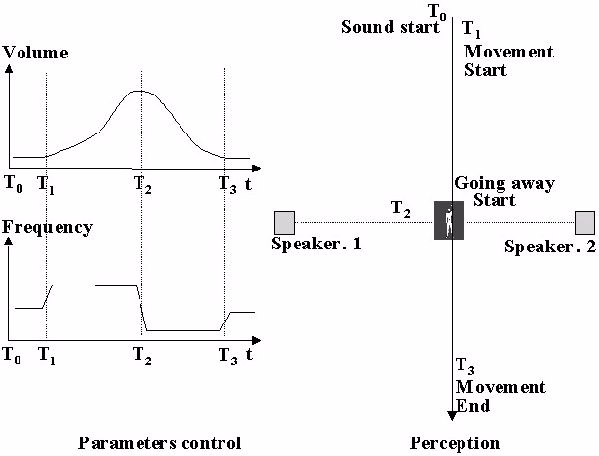

L’acusmetria nasce da un gesto, semplice come lo scorrere di una matita su un foglio, tradotto in suono. È lo studio delle correlazioni tra i modelli sonori ascoltati e le forme geometriche evocate all’ascolto per analogia. Questa analogia si basa sui rapporti tra i parametri acustici e geometrici: dell’intensità per la distanza, della frequenza per l’altezza e della stereofonia per il movimento laterale (fig. 1).

Così come molteplici sono le modalità con cui si compie il gesto di tracciare un segno sulla carta, variando tempo, accelerazioni, spessore dei tratti, anche i parametri acustici (frequenza, modulazioni, velocità, dinamiche) si articoleranno di conseguenza.

Si tratta di un fenomeno sinestetico evocato uditivamente e ancorato all’esperienza della percezione visiva. Prima di avere un nome e di poter rispondere a leggi definite, questa tecnica era un personale sistema compositivo scaturito da un insieme di suggestioni diverse.

Avevo iniziato creando con i suoni alcune figure geometriche semplici, attraverso l’organizzazione di linee e punti in uno spazio che chiamai poi “foglio uditivo”.

Il rapporto con la geometria che cercavo di stabilire attraverso i miei oggetti sonori poi denominati As (acousmetric shape), mi aveva riportato sulla strada del vecchio Pitagora, che divideva i suoi discepoli in “acusmatici” e “matematici”.

Il termine “acusmatico” fu nel ‘900 riproposto e introdotto nel lessico musicale da Pierre Schaeffer – noto come il padre della musica concreta – per indicare genericamente ogni rumore che si intenda senza vedere le cause dalle quali deriva.

Nel mio caso però, ciò che mi proponevo era di codificare delle forme precise, ecco perché decisi di mantenere la radice acous- e cambiare la desinenza in -metria (da metron, misurare).

***

E' stato avviato un progetto di ricerca sulle basi neurofisiologiche del fenomeno acusmetrico in collaborazione con l'Università di Parma, per interessamento del Prof. Giacomo Rizzolatti, padre dei neuroni specchio, il cui responsabile Scientifico è il Prof. Vittorio Gallese.

CITAZIONI

L'acusmetria ha buttato per aria il castello metafisico della sensorialità.

Carlo Sini

Ritengo la sua ricerca di grande interesse. Ha risvegliato in me con nostalgia tanti discorsi che mi faceva Luigi Nono.

Massimo Cacciari

Stiamo assistendo ad un cortocircuito sensoriale, è quindi necessario mettere in armonia contenuti di ambiti diversi.

Andrea Branzi

Acusmetrica è la condizione naturale quotidiana di ogni Io ascoltante. Questo Re è sempre stato nudo ma, al solito, bisognava che qualcuno se ne accorgesse.

Giorgio A. Riva

***

PRESS

Rai Radio 1 - Metrò - podcast (02/03/2011)

Intervista a F. Rampichini di Paolo Notari

Rai Radio 1 - Fratelli d'Italia podacst (31/1/2011) podcast

Radio Classica 28/1/2008 Intervista a F. Rampichini di R. Belgiojoso podcast

Tabloid 4/ 2005 La libreria di Tabloid ("Acusmetria. Il suono visibile" di P. Paganini)

Tribuna stampa (01/2005) Libri - Acusmetria di S. Annibaldi

Corriere del Mezzogiorno (22/10/2004) I Festa dell'archittettura - D. Lama

Il Mattino (21 ottobre 2004) I valori dell'architettura

Suonare News (09/2004) Capriccio spaziale di A. Bertolini

Modo (luglio/agosto 2004) Acusmetria-Geometria del suono di A. Fanelli

Il Manifesto (Alias, 26/6/2004) Che bell'edificio di mattoni sonori di M. Sebregondi

Wayfitness (05/2004) Ascolta questa bella geometria

Radio 24 (8 agosto 2004) Intervista a F. Rampichini di M. Daghini

Radio 24 (11 maggio 2004) Intervista a M. Maiocchi di S. Coyaud

Corriere della sera Sette, 29 aprile 2004) Studi di frontiera - l'Acusmetria - A. Pasini

Foglio dell'Institutum Pataphysicum Partenopeium n° 2 (2003) Acusmetria - racconto di Marco Maiocchi

Il Teatro Temperato - racconto (2005) di Giuseppe Crotti

Fig. 1 - Lo spazio acusmetrico: Π (mov. laterale); A (altezza); I (profondità).

INTRODUZIONE al volume

di Francesco Rampichini

Intorno alla metà degli anni ’80, la fisica Monica Zamboni mi parlò per la prima volta di quelle singolari leghe intermetalliche a base Nichel-Titanio (NiTi) chiamate “materiali a memoria di forma”, per la cui produzione si parla di una “educazione del materiale” mediante un trattamento che permette di memorizzare la forma finale che verrà assunta. L’esempio più semplice è un elemento attivo a forma di molla elicoidale che debba chiudersi completamente a caldo. Questa capacità di modificare il proprio stato al variare della temperatura, sfruttata per assolvere particolari funzioni (sensore/attuatore), le colloca nella categoria dei "materiali intelligenti”, con caratteristiche di superelasticità ed elevata capacità di smorzamento delle vibrazioni. Alcuni aspetti delle loro proprietà mi colpirono immediatamente per l’analogia con i problemi che stavo cercando di risolvere sul piano acustico.

L’associazione con “oggetti sonori” che potessero evocare un disegno identificabile fu spontanea.

Solo anni dopo tuttavia arrivai a formalizzare l’intento di stabilire un rapporto biunivoco tra suono e segno grafico (punto, linea) avviando tentativi di creare materiali sonori che evocassero forme geometriche più o meno complesse, senza ancora intravedere in che modo avrei potuto utilizzarle.

L’avvento dell’era informatica aprì un varco in questo intento. Grazie ai nuovi sequencer MIDI potei iniziare a progettare i materiali di più semplice concezione: un punto, un segmento di retta, alcune linee curve.

L’idea di poter pervenire alla descrizione di spazi audiografici a partire da tali elementi attivò un processo compositivo che sfruttava queste prime analogie con la geometria piana.

Diversi anni più tardi arrivai a definire Acusmetria il principio sul quale questi processi si basano e forme acusmetriche gli oggetti sonori in essi implicati.

Sottoponendoli all’ascolto da parte di soggetti non informati constatai di poter rappresentare un triangolo in modo praticamente inequivocabile, soprattutto nella modalità puntiforme, poiché le linee, cioè i suoni continui, ponevano maggiori problemi di natura percettiva. Seguirono quadrati, rombi, pentagoni, esagoni, ettagoni, ottagoni, ellissi...

Giunto per questa via alla costituzione di un primo strumentario acusmetrico, iniziai a compiere tentativi di sovrapposizione, il primo dei quali riguardò un cerchio ed un triangolo: l’impatto dal punto di vista psicoacustico fu forte.

Mi resi conto che le sensazioni prodotte all’ascolto erano più complesse dell’esperienza ottica: il fenomeno, sul piano della percezione uditiva, era affatto nuovo e induceva un senso di delocalizzazione spaziale a me sconosciuto, imputabile come scoprii in seguito al funzionamento dei meccanismi di ritenzione mnemonica dei punti di riferimento uditivi.

Per quanto ne sapevo, nessuno si era mai occupato di costruire un “alfabeto” di questo genere, né di stabilire una relazione geometrica diretta tra suoni e segni grafici.

Il côté scientifico di queste esperienze cominciò ad appassionarmi più tardi, anche grazie alle conversazioni con l'architetto Ettore Lariani che mostrava un interesse trasversale per questi argomenti, dato dal suo operare nella modellazione spaziale e dalla sua viva curiosità per il mondo dei suoni.

Entrambi appartenenti alla generazione formatasi senza i computer e cresciuta nel pieno della grande rivoluzione informatica degli anni ’80/90, ne avevamo vissuto l’irresistibile sviluppo sperimentando giorno per giorno il rapido confluire dei metodi di lavoro tradizionali verso quell’unicum mediatico instaurato dalla diffusione capillare del Pc. Architettura e musica, design e psicoacustica divennero i temi principali dei nostri scambi.

Nel 1999 Lariani, docente alla Facoltà del Design del Politecnico di Milano, mi propose per un incarico didattico in un ambito che definimmo "forma/suono" e che da quel momento condividemmo, organizzando e sviluppando le ricerche in un contesto universitario stimolante, insieme a centinaia di studenti senza il cui impegno non saremmo forse giunti a elaborare l’approccio all’ipertesto esteso che chiamammo media_FORMASUONO.

Sempre al Politecnico di Milano avvenne l'incontro con il fisico Marco Maiocchi. Con lui si instaurò subito un rapporto di collaborazione sostenuto dal comune interesse per le sinestesie.

Quando io e Lariani parlammo dell’acusmetria a Maiocchi – esperto di strutture e appassionato di musica – non solo ne colse immediatamente i presupposti fondamentali, ma iniziò a suggerire e progettare esperimenti che produssero gli essenziali contributi della terza parte di questo volume.

Qui sono esposti i principi della materia. Abbiamo indicato dei percorsi, guardando ai fatti nella loro integrità fenomenologica, al di là del gioco delle codificazioni ed oltre la loro integrazione nelle teorie. Ecco ad oggi lo stato dell’arte.

Fig. 2 - Depth perception through Volume and Pitch control.

T e s t a c u s m e t r i c o (download v e r. 0.1)

ALCUNE TESI DI LAUREA SULL'ACUSMETRIA

Corsi in Facoltà Universitarie e Conservatori di Musica. Qui elencate, alcune fra le tesi e i testi sull'argomento di cui si ha notizia.

IL MODELLO ACUSMETRICO

a.a. 2010-2011 - Università di Roma Tor Vergata - Facoltà di Ingegneria

di Mario Salvucci - rel. Bruno Gioffré

LA MACCHINA ACUSMETRICA TOTALE

a.a. 2004-2005 - Politecnico di Milano - III Facoltà del Design - rel. Marco Maiocchi - co-rel. Ettore Lariani, Francesco Rampichini

di Christian Sciascia

ACUSMETRIA: UN NUOVO CODICE

a.a. 2003-2004 - Politecnico di Milano - Facoltà di Architettura - rel. Pier Federico Caliari - co-rel. Francesco Rampichini

di Erika Gagliardini

MUSEO ACUSMETRICO DESIGN - MAD

a.a. 2002-2003 - Politecnico di Milano - Facoltà del Design - rel. Ettore Lariani - co-rel. Francesco Rampichini

In 4 volumi:

Progettazione acusmetrica integrata negli spazi allestiti di Nicola Moioli

Progetto architettonico di recupero dell'area industriale dismessa di Nicola Seta

Allestimento e organizzazione degli spazi interni ed esterni di Federico Vedani

Progetto dell'immagine coordinata e dei sistemi di comunicazione di Martino Pannofino

CASSE ARMONICHE: LUCE COLORE E MATERIA

a.a. 2009-2010 - Politecnico di Milano - Facoltà del Design di Daniela Leoni - rel. Salvatore Zingale

ACUSMETRIA

3a Fiera Internazionale dei Giovani Inventori New Dehli, India, dicembre 2006

Autori: Stefano Bolzonella, Boris Nani, Fabio Turi - Tutor universitari: Ettore Lariani, Marco Maiocchi, Francesco Rampichini

Docente: Maristella Galeazzi (Liceo Scientifico "E. Fermi" - Cantù)

Scheda descrittiva

Alcune Tesi nell'archivio:

Politecnico di Milano - OPAC generale Servizi Bibliotecari

Altre Tesi:

Viaggio nella città del suoni

L'immagine sonora

Il silenzio del suono (manuale di introduzione al design acustico, Laura Turra, 2015)

ALCUNI MEETING SULL'ACUSMETRIA

20 marzo 2005 - h 16,15

Seminari di cultura matematica

Dipartimento di Matematica del Politecnico di Milano - Piazza Leonardo da Vinci, 32

Seminario dal titolo: "Acusmetria. Il suono visibile" - relatori: F. Rampichini (musicista), M. Maiocchi (fisico), E. Lariani (architetto)

18-22 novembre 2004

Futurshow

Fiera di Milano, stand I.NET, loop projection di U.V.A., danza acusmetrica di Francesco Rampichini - Collaborazione e coordinamento: Ettore Lariani, Marco Maiocchi.

11-12 Novembre 2004

The 12th International Forum on Design Management Research & Education - The 2nd Annual Conference - Institute for Industrial Policy Studies - Brand Management Institute - 3rd Annual Conference of Brand Management Institute

Seoul, Korea

E. Lariani, M. Maiocchi, F. Rampichini: "Acousmetric Branding", pubblicato negli atti del convegno insieme ai file sonori per la fruizione

22-23-24 ottobre 2004

Frame & Mutations - Festa Europea dell’Architettura, Napoli

(dal catalogo) Frame & Mutations - visioni di architettura (ed. Aracne)

26 giugno 2004

Università internazionale del secondo rinascimento

Conferenza di Marco Maiocchi, Francesco Rampichini, Ettore Lariani - Introduzione di Armando Verdiglione - Senago, Villa San Carlo Borromeo

21 giugno 2004

Dipartimento di Matematica "F. Brioschi" - Politecnico di Milano

Acusmetria, seminario organizzato da prof.ssa Tullia Norando. E. Lariani, M. Maiocchi, F. Rampichini

12 maggio 2004

Triennale di Milano - Festival dell'Architettura - Presentazione dell'Acusmetria

***

In fase di definizione, un progetto di ricerca sull'Acusmetria in collaborazione con il Prof. Giacomo Rizzolatti, padre dei neuroni specchio.